He loved nature, animals, and the outdoor life; he was a friend to children, a defender of civil liberties, a great orator, a rancher, and a “just judge;” he was an adventurous traveler, a dedicated husband and father, and if it were not for Robert Wilbur Steele, our children would be attending a school called Lake View.

Robert was born in Ohio in 1857. His family moved to Denver in 1870, primarily for Robert’s health. They lived at Sixteenth and Stout, at the time the heart of Denver’s residence district. His father, Dr. Robert K. Steele, was a Civil War surgeon, organized the Colorado Medical Society, was the dean of the medical department and a professor of surgery at the University of Denver, and health commissioner for the City of Denver. Upon his death, in 1893, Steele Memorial Hospital was named for him.

In 1877, Robert and seven Arapaho High School classmates composed Colorado’s first graduating class. He then played semi-pro ball, as left fielder, in Denver’s only uniformed club, the Brown Stockings, before attending law school in Washington, D.C.

Admitted to the Colorado bar in 1881, Robert was a county clerk, Denver district attorney, county court judge, and Colorado Supreme Court judge. His firm, Steele and Malone, had offices in the Tabor Opera House, known as the finest business block in the West.

When Robert and his wife, Anna, built their house at Eleventh and Washington Streets, they were well outside the city limits, and cowboys herded cattle nearby. By 1886, however, city water and gas service were available. They raised five children there, two of whom lived to adulthood.

Robert had spent childhood summers at a cousin’s ranch in the San Luis Valley, nurturing a love of working the land. It’s no surprise, then, that in 1888, Robert homesteaded a 160 acre ranch located between Exposition and Mississippi Avenues, and from Fairmount Cemetery westward.

His influence in the courts can be seen today. In Judge Steele’s day, children were treated no differently than adults in court. Judge Steele’s concern for children moved him to establish a Juvenile Field Day in court. He wanted “not to punish, but to help” children, and his successor, Judge Ben R. Lindsey, known as the father of the juvenile court system, cited Steele as an influence and inspiration.

Concern for civil liberties and upholding the Constitution brought Robert nationwide acclaim when his was the only dissenting opinion in the Moyer case, involving suspension of the writ of habeas corpus.

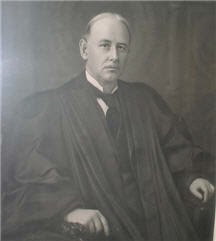

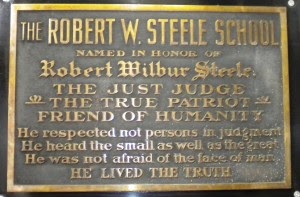

Upon Robert’s death of a heart attack on October 12, 1910, Governor John Shafroth ordered flags flown at half-mast for four weeks, and Colorado government offices closed while his body lay in state at the capitol. It was decided that Lake View, a school in the planning stages, should be named Steele, and his widow, Anna, donated a plaque, his portrait, a flag, and 600 books in his honor to the school named in his honor.

Robert W. Steele’s memorial window hangs in the Supreme Court Room of the Colorado State Capitol.

There are two Robert W. Steeles prominent in Colorado history; the other Steele was a territorial governor in 1859, our Robert W. Steele was a Colorado Supreme Court justice, and so research can be confusing. One Denver history book says that he was both governor and judge, although the governor was in office when our Robert was two years old. Even the DPS web site gives the governor’s birth and death dates as those of the judge’s. I was able to get correct information from the book Robert Wilbur Steele, Defender of Liberty, written in 1913 by Walter Lawson Wilder. This rare book was generously donated to Steele’s library in 1990 by Sara and Jerry McCarthy.

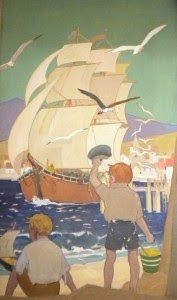

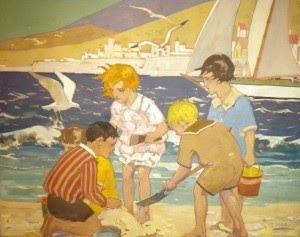

To step into Steele’s Kindergarten rooms is to step back in time. The fireplace tiled with animals and amphibians, the nursery rhymes depicted in stained glass on the doors, and the enchanting Allen True murals of old-fashioned children at play conspire to take you away to an earlier day. The entire effect is charming, but it is the True murals that really make one stop and look around.

Steele Elementary joins an impressive list of notable and historic Denver buildings that are graced by Allen True murals. In their book, “Denver the City Beautiful,” historians Tom Noel and Barbara Norgren call True, “Colorado’s most noted native artist.”

Muralist Allen True (1881-1955) was born in Colorado Springs, studied art in Washington, D.C. and London, and began his career as a highly regarded magazine illustrator. In 1910, True moved to Denver where he made his mark on local art and architecture with murals on many public, and several private, buildings.

Sadly, some Allen True murals have been lost to building demolition, but his work can still be seen in the following places:

True was a member of the Cactus Club, a group of artists, poets, professional men, and community leaders who shared an interest in pursuits both intellectual and Bohemian, and he contributed to the group’s architecturally fascinating clubhouse, now demolished, at 444 14th Street. His official studio was at 2393 Raleigh St., but True spent a good deal of time in the mountains, both relaxing and working. During restoration of the Central City Opera House, the artist discovered and restored original frescoes.

We in the Steele community are fortunate to have such significant artwork in our school, so if you haven’t been in Steele’s ECE room recently, or, worse, not at all, it’s well worth the trip downstairs to take a trip back in time

The information for this article came from “Denver the City Beautiful,” by Thomas S. Noel and Barbara S. Norgren, 1987.

Called one of the finest examples of Art Deco architecture in the state, Steele School actually started as a neo-classical structure made of buff brick and red sandstone. Built in 1912 for $116,030.98 (that price included the land and equipment-imagine!), it opened in the fall of 1913 with 223 pupils in Kindergarten through eighth grade, and six teachers.

Built during Denver’s “City Beautiful” movement, which brought us Speer Boulevard and Civic Center Park, Steele School and Marion Street Parkway were to be a component of a never fully realized link between Washington Park and Cheesman Park. Steele’s architect, David Dryden (1861-1915), was involved in the designing of 23 DPS schools, including Evans School-that abandoned school at Eleventh and Acoma, Dora Moore Elementary, and North High School.

Like all DPS schools at the time, the custodian lived on the grounds, in what is now part of a kindergarten room. The other part of the kindergarten room, and what is now Room 006, was used as an auditorium. Room 107 was intended to be the library (there might be bookcases behind the chalkboards).

By the late 1920s, Steele had more than doubled its population to 523 students and expansion was needed. Popular thought at the time was that buildings should reflect the time in which they were built, and so architect Meryll Hoyt (1881-1933) replaced Steele’s Roman, Greek, and Italian Renaissance elements with the Art Deco building we have today. Hoyt also designed the neo-gothic Lake Junior High and the Spanish Revival Park Hill Branch library.

When it re-opened on September 16, 1929, Steele had 18 classrooms, a library, an auditorium, a gymnasium, and a Kindergarten. There were 535 students and 15 teachers. In 1995, the Denver Landmark Commission designated Steele School as a Structure for Preservation.

Every reader knows that the characters in books come alive in our hearts and minds. In Steele’s library, cherished characters have gone a step further: a collection of classic characters have stepped right out of the books and are on display in the form of the handmade dolls in the Caroline Harrison Memorial.

Who was Caroline Harrison? Well, it’s time that you met her, because for generations of Steele students, she was the librarian who enthusiastically brought the love of reading into their lives. From 1933 until 1963, she shared her sense of humor, her dedication to children, and her love of literature with the Steele community.

News clippings from the time describe “Miss Caroline” as “…one of the most endearing friends of children.” “I am sure you can never realize how much it meant to me to know Miss Harrison.,” wrote a former pupil, a sentiment shared in many letters from her former students. Although Miss Harrison had taught library instruction at Stevens, Valverde, and Barnum schools, Steele must have felt like home, because she stayed for thirty years. She left in 1963, only after being persuaded by the superintendent and the director of Library Services to accept the Coordinator of Elementary Library Instruction position.

Miss Harrison’s spirit and sense of humor were on full display in this note that she wrote on bright holiday stationery and put in each teachers’ mailbox one Christmas:

Dedicated to the new English Program of the D.P.S., and to the teachers what learn the kids English,–how she is spoke, and writ.

The Kings have came, the kings have went,

The carols have been sang,

The chilly halls,

With many calls,

Have rang, and rang, and rang.

But now, praise be, the work is did,

The kids have homeward ran,

So hip-hooray,

Leave us be gay,

Vacation has began!

‘Bye, dahlings,-

CH

Caroline Harrison was born in Alabama in 1902. She graduated from Central High School in Pueblo, received a life teaching certificate from Colorado State Teachers College (now the University of Northern Colorado), a bachelor of arts degree from the University of California, Berkeley, and a masters degree from the University of Denver. She lived in the Steele neighborhood, at the Country Club Garden apartments, 23 South Downing St.

Upon her death in 1965, former students, parents, and teachers who had known Miss Harrison funded a memorial in her name. A total of $1200 was collected-a tidy sum in the days when letters were mailed for a nickel, a gallon of gas cost 31 cents, and a new Ford Mustang could be had for $2500. Part of the money was used to buy the Simpich dolls that decorate our library today. The remainder was used to create a book collection.

Simpich Character Dolls is a Colorado Springs company that has been making handmade dolls since 1952. The Steele collection includes Robin Hood, Alice in Wonderland, Winnie the Pooh and Christopher Robin, Scrooge and the Cratchett family, Tom Sawyer, and Huck Finn.

The following was read at the dedication of Caroline’s memorial in 1967:

The parents and children out of Steele School’s past give to you, the children of the present, these storybook characters. Enjoy them through your grade school years and when you leave they will remain for the children of the future to treasure in their turn.

It is our hope that this gift, given in memory of Caroline Harrison, will be the tie that binds all Steele children, past, present, and future together in a common love of the storybook characters that dwell in the pages of the books Caroline Harrison loved so well.

So, the next time you are in our library, stop to visit the dolls that represent the spirit of a Steele treasure, Miss Caroline Harrison.